The Gentleman of Brunello.

Franco Biondi Santi Remembered.

If you know of Brunello di Montalcino, the Tuscan benchmark for world-class wine, it is due to the efforts of Franco Biondi Santi and his family. The stately “gentleman of Brunello” passed away in April of 2013 at the age of 91, less than a year after we met at his beloved ancestral estate Tenuta Il Greppo.

If you know of Brunello di Montalcino, the Tuscan benchmark for world-class wine, it is due to the efforts of Franco Biondi Santi and his family. The stately “gentleman of Brunello” passed away in April of 2013 at the age of 91, less than a year after we met at his beloved ancestral estate Tenuta Il Greppo.

To arrive at his home, we passed through a majestic evergreen tunnel of 300-year-old cypress trees and I found myself wondering how many before had traversed this narrow tree-lined lane. In Mr. Biondi Santi’s autobiography he recounts his perilous trip home from the French border during World War II. “In my mind’s eye” he wrote, “I can still see my father waiting for me at Il Greppo as I walk down the cypress-lined avenue.”

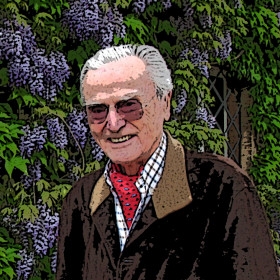

Mr. Biondi Santi emerged from the front portico of Il Greppo, grown green and lavender with Ampelopsis vines and flowers. While much has been written about Mr. Biondi Santi’s impact on the wine world, my prevailing memory of him is his piercing eyes and curious smile.  The corners of his mouth were perpetually curled up, as if he were fruitlessly fighting to conceal this smile. When he found his remarks amusing, as he often did, the smile deepened, forming dimpled cheeks that compressed the well-worn laugh lines around his eyes. He had about him the good-humored countenance of a man at peace with himself and the world.

The corners of his mouth were perpetually curled up, as if he were fruitlessly fighting to conceal this smile. When he found his remarks amusing, as he often did, the smile deepened, forming dimpled cheeks that compressed the well-worn laugh lines around his eyes. He had about him the good-humored countenance of a man at peace with himself and the world.

We visited vineyards planted exclusively with Sangiovese Grosso, a grape species more commonly known as “Brunello.” In the nineteenth century a typical Tuscan vineyard might contain a dozen different grape varieties, both white and red, that were harvested and fermented together to make short-lived wines of passable quality.

In the mid 1800’s Franco’s great, great grandfather Clemente Santi set out to isolate the grape clone best suited to the soil of Montalcino and the making of wines with great aging potential. In the solitude of these vineyards it’s easy to imagine the spirit of Clemente and those who followed keeping silent vigil over the grapevines of Il Greppo.

At the time Clemente Santi was painstakingly searching for superior grape clones and typical Italian winemakers were producing simple field blends, the French were classifying the great chateaus into a quality hierarchy called the “Official Bordeaux Wine Classification of 1855.” At the Universal Exposition of Paris where the classification was unveiled, Clemente Santi received recognition, not for his work with wine, but for his efforts with brick production techniques. However his efforts and dedication in the vineyard were also soon recognized and in 1865 Clemente Santi introduced for the first time, a wine labeled “brunello.”

Clemente’s daughter Caterina married a nobleman named Jacopo Biondi, resulting in the double surname Biondi Santi that endures today. At a time when sweet white wines were popular in the region, Caterina’s son Ferruccio carried on the vinification experiments of his grandfather Clemente and (a century ahead of his time) he created a dry, age-worthy, single varietal wine – the first to bear the name “Brunello di Montalcino.”

Contrary to the customs of Chianti, Ferruccio instituted strict clonal selection, new fermentation procedures, and lengthy aging requirements. He identified the best vines in the vineyard and in superior vintages these grapes were harvested exclusively for a special “Riserva” wine, the first in 1888, followed quickly by another in 1891.

When Ferruccio died in 1917, Il Greppo was handed over to his sons Tancredi and Gontrano, who at that time were fighting in the First World War. In 1922, the year Tancredi’s son Franco was born, Tancredi bought out Gontrano’s interests in Il Greppo. Under Tancredi’s tutelage the wines of Biondi Santi earned high praise, and he expanded the production of Brunello di Montalcino by encouraging his neighbors to plant their vineyards with the Brunello clone. However Tancredi’s tenure suffered severe hardships from repeated outbreaks of the vineyard devastating phyloxera, economic recession, the advent of fascism, and two world wars.

During World War II, as German soldiers made daily raids in the area and the American front line advanced from the south, Tancredi and his son Franco labored through the night in near total darkness, building a brick wall to conceal their precious library of Brunello Riserva. The wine was saved, including the original bottles of 1888 and 1891, and I had the privilege of visiting those rare treasures over 60 years later with Franco by my side. Franco helped rebuild Il Greppo after the devastation of World War II and he assumed control upon his father’s passing in 1970.

During World War II, as German soldiers made daily raids in the area and the American front line advanced from the south, Tancredi and his son Franco labored through the night in near total darkness, building a brick wall to conceal their precious library of Brunello Riserva. The wine was saved, including the original bottles of 1888 and 1891, and I had the privilege of visiting those rare treasures over 60 years later with Franco by my side. Franco helped rebuild Il Greppo after the devastation of World War II and he assumed control upon his father’s passing in 1970.

During Franco’s tenure at Biondi Santi, the popularity and production of Brunello di Montalcino expanded dramatically. In 1971 a mere 385 acres were planted in the appellation. That number climbed to roughly 5,200 acres under vine by the time of Franco’s passing in 2013. Franco became the stalwart protector of the wine he lovingly referred to as “my brother Brunello” and successfully defeated efforts to change the strict production guidelines that were established by his family.

When Italian wine laws were formalized in 1968, the Denominazione di Origine Controllata (DOC) created for Brunello di Montalcino was based on the guidelines established by the Biondi Santi family. In 1980, when a higher quality designation was called for, Brunello di Montalcino became the first wine in Italy awarded Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita (DOCG) status.

Traditional Brunello production calls for four years or more aging in a combination of barrel and bottle before release (the reserve wines age an additional year). Montalcino wine cellars are different than most because large areas are required to store the bottled wine before labeling and release. In the cellars of Il Greppo I meandered past large bins of bottles with nothing more than a chalk mark to indicate their precious cargo.

I stood in the shadows of imposing Slavonian barrels placed here by Ferruccio in 1870. I might have felt insignificant in this hallowed space if not for the inclusive warmth of our host. Franco Biondi Santi was both gracious and gregarious, regaling us with lively stories and his good-natured humor.  He pointed out a large bin that held over 300 bottles of 1997 Riserva stacked one on top of the other. Like a mischievous schoolboy he reached down to the bottom of the stack and with dramatic flair, snatched a bottle out of its precarious perch. My wife Caroline screamed in disbelief, certain the remaining bottles would come crashing down around us. I showed much more restraint, I merely fainted.

He pointed out a large bin that held over 300 bottles of 1997 Riserva stacked one on top of the other. Like a mischievous schoolboy he reached down to the bottom of the stack and with dramatic flair, snatched a bottle out of its precarious perch. My wife Caroline screamed in disbelief, certain the remaining bottles would come crashing down around us. I showed much more restraint, I merely fainted.

Franco, amused at his playful ruse, smiled broadly as Caroline laughed and hooked her arm inside his elbow to draw him close. Looking down at her he said, “Did you know that my wife doesn’t drink wine?” I’m never at a loss for words, but at that moment language deserted me. I stood awestruck by the notion that anyone could live a life surrounded by such profound wine and never be tempted to drink it.

Franco led us to a room lined with framed documents detailing much of the Biondi Santi family history and by extension, the history of Brunello di Montalcino.  He proudly pointed to a framed Wine Spectator article regarding the 12 greatest wines of the 20th century. Biondi Santi’s 1955 Brunello Riserva was the only Italian wine on the list, securing its rightful place in history alongside such notable classics as 1900 Chateau Margaux, 1921 Chateau d’Yquem, 1945 Chateau Mouton Rothschild and 1947 Chateau Cheval Blanc.

He proudly pointed to a framed Wine Spectator article regarding the 12 greatest wines of the 20th century. Biondi Santi’s 1955 Brunello Riserva was the only Italian wine on the list, securing its rightful place in history alongside such notable classics as 1900 Chateau Margaux, 1921 Chateau d’Yquem, 1945 Chateau Mouton Rothschild and 1947 Chateau Cheval Blanc.

On a table near the article stood three bottles of Biondi Santi wine, a recently expelled cork perched on top of each. “Ahh, the tasting,” I thought, “what a fitting end to a wonderful morning.” But our day was far from over. Franco led us past the table and up the stairs to his private study. Here we found a table set with half a dozen glasses at each seat and a booklet titled “Tenuta Greppo, Franco Biondi Santi, Wine Tasting for Don and Caroline Carter.”

It probably goes without saying that the wines were sublime (the ‘97 Brunello Riserva is a monolithic, aromatic masterpiece), yet I found it hard to give them their deserved attention because the rarest treasure in the room was Franco himself. He sat at the head of the intimate table with a small window high on the wall behind him. The descending light created an ethereal aura around Franco that seemed to radiate from, and bind him to, the vineyard outside.

It probably goes without saying that the wines were sublime (the ‘97 Brunello Riserva is a monolithic, aromatic masterpiece), yet I found it hard to give them their deserved attention because the rarest treasure in the room was Franco himself. He sat at the head of the intimate table with a small window high on the wall behind him. The descending light created an ethereal aura around Franco that seemed to radiate from, and bind him to, the vineyard outside.

For the next few hours Franco talked glowingly of his family, his land, and his wine. He never grew tired of my questions and seemed to relish the telling of his story. I puckishly asked him about the modern movement towards non-native grape varieties possibly being allowed in Brunello di Montalcino. He looked at me sideways, a wry smile crossed his face and he thoughtfully replied, “It has taken 150 years for people to realize Baron Ricasoli’s Chianti recipe was wrong and my grandfather was right. Sangiovese Grosso will remain the only grape allowed in Brunello as long as I’m alive.”

We returned to his cellars and Franco unlocked the door to a closet-sized room. I wondered if this petite doorway was the one covered with bricks in 1944.  The two of us squeezed into the tiny space, Franco picked up a dusty bottle from the top bin and held it before a small lantern. Here in this ancient room in the cellars of Il Greppo, Franco revealed his prized possession, the last two bottles of Ferruccio’s 1888 wine, the first to bear the name Brunello di Montalcino.

The two of us squeezed into the tiny space, Franco picked up a dusty bottle from the top bin and held it before a small lantern. Here in this ancient room in the cellars of Il Greppo, Franco revealed his prized possession, the last two bottles of Ferruccio’s 1888 wine, the first to bear the name Brunello di Montalcino.

Although we talked about the technical aspects of aging wine, the atmosphere in that room was purely magical. The warm lantern light gave a spiritual glow to the 125-year-old wine in Franco’s hands, but the image etched into my memory remains the radiant expression on his face.

Franco has taken his place alongside Clemente, Ferruccio and Tancredi, the spiritual sentinels that inhabit the heavenly vineyards of Il Greppo. Franco Biondi Santi and the cellars of Il Greppo have become one. The air is his breath, the barrels are his bones and the wine is his blood. He will be missed in this world, but know in your heart you can visit him still, you need only open a bottle of his remarkable wine.

Don, what a beautiful story. Thank-you so much for sharing this very intimate visit. Craig.

It remains the most memorable day of my career (although there have been many great days in my career that I can’t remember at all).

What a wonderful story and amazing, memorable experience! 2 bottles left of 1888…..what a celebration of history that is!