Pass The Toast – The Maillard Reaction in Wine Barrel Toasting.

Chapter Thirteen, Part Four.

Not long after Kikunae Ikeda discovered umami, a French physician by the name of Louis Maillard (pronounced my-ARD) described the chemical reaction that takes place when amino acids combined with sugar are exposed to heat. This transformation, once known simply as browning, is now called the Maillard reaction. (It is rumored the original name, browning, was named after Maillard’s cook, Dorothea Brown.)¹

Not long after Kikunae Ikeda discovered umami, a French physician by the name of Louis Maillard (pronounced my-ARD) described the chemical reaction that takes place when amino acids combined with sugar are exposed to heat. This transformation, once known simply as browning, is now called the Maillard reaction. (It is rumored the original name, browning, was named after Maillard’s cook, Dorothea Brown.)¹

The Maillard reaction is what turns toasted bread a golden brown and creates the seared crust on protein rich foods like steak or chicken. I think my neighbor was grilling some protein rich food last night because I heard him say, “Hey Carter. Get your dog out of Maillard!”

By now you’re probably wondering what grilled bratwurst has to do with winemaking. It turns out oak barrels are also subject to the caramelizing effect of searing heat. It’s not actually caramelization but a process very much like it. Caramelization occurs when sugars are exposed to heat. The more complex Maillard reaction takes place when sugar and amino acids are heated. Caramelizing just rolls off my tongue easier than Maillardizing, and I’m all about easy now that I’m on my third glass of Malbec.

To assemble a barrel, the staves are heated over an open fire of oak timbers. This gives the wood the flexibility to bend into shape, whereas I need a full hour on a stairmaster to bend into shape. As you can imagine, heat this intense can burn the wood surface, which barrel coopers refer to as barrel char or barrel toasting. Like seasoning, toasting curbs some  of the unruly plank smells, herbaceous aromas, and wood resin odors that can have a negative impact on wine. But barrel toasting does more than cover up disagreeable flavors; it produces compounds in oak that add a whole slew of agreeable esters to wine.

of the unruly plank smells, herbaceous aromas, and wood resin odors that can have a negative impact on wine. But barrel toasting does more than cover up disagreeable flavors; it produces compounds in oak that add a whole slew of agreeable esters to wine.

The Maillard reaction produces vanilla-like esters known as lactones which coincidentally, was the name of my teenage acapella band. The lactones, while not overly sweet or cloying, do add faint impressions of sweetness to the finished wine. Much of the smoky, roasted qualities found in wine are a result of barrel toasting. Kiln drying oak should not be confused with toasting oak. One is the slow drying of oak in an oven; the other is raising a glass to oak in salute.

The degree of toasting affects the types of flavors generated, and as the toasting level increases, so does its impact on the developing wine. Winemakers can order their barrels with light, medium or heavy toast to suit their preferences. Choosing the correct oak is like choosing the right suit. Winemakers may choose heavy toast (think Armani suit) or choose no oak (think birthday suit). As you might expect, “virgin wine” refers to wines that have never seen wood.

Lightly toasted oak increases sweet esters such as vanilla, caramel, and holiday spice flavors like nutmeg, clove, and cinnamon. Medium toasting oak barrels has more impact on the aromas in wine. Vanilla, honey, caramel and toasty, roasted nut aromas are more pronounced. Wine may develop nuances of smoked meats, burnt embers, and roasted coffee or espresso when aged in heavy toast barrels. These flavors are often described as smoky, charred, toasty, roasted or burnt. Oddly enough, smoky, charred, toasty, roasted and burnt are the same terms I use to describe my brother-in-law, but as far as I know he’s never been inside a wine barrel.

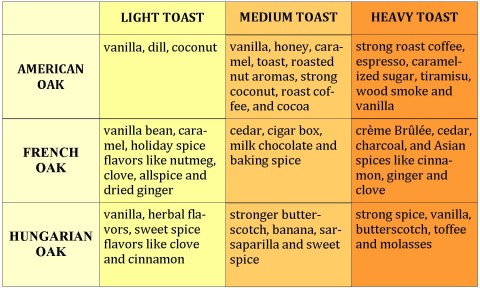

French, American and Hungarian oak all react differently when toasted. Some of the most common traits imparted to each species are outlined in the following chart.

When oak interacts with wine, the esters created vary with the different grape varieties. An American oak barrel may transmit chocolate nuances to a Washington state Merlot, and vanilla or coconut nuances to a California Zinfandel. White wines are more likely to develop flavors of honey, vanilla, baked apple, caramel, toasted marshmallow, buttered toast, or roasted nuts.

Keep the Maillard reaction in mind when pairing oaky wines with dinner. Regardless of the grape variety, pronounced toasted oak flavors in wine share an affinity with the browned surfaces of grilled foods, especially those cooked over wood chips. Tonight I prepared a seriously seared pork tenderloin on the grill and my wife and I paired it with a heavily oaked Rioja Gran Reserva. The body was amazingly smooth, luscious and voluptuous, and the wine was pretty good too.

¹ I just made that up. Dr. Maillard’s cook was actually named Searing.